1. What Is Reality?

Cosmology & Origins: A Question That Changes Everything

You wake up one morning and the world looks exactly as it always has. Your coffee is still warm. The light still enters your window at the same angle. The news is still full of the same patterns of human complexity and failure and occasional grace.

And yet something has shifted.

Not in the world. In you. A question that won’t leave you alone:

What is actually real?

It sounds like the kind of question philosophers ask in late-night conversations, the kind you might dismiss as impractical or abstract. And yet here you are, in your fifth or sixth decade, asking it seriously. Not performatively. Not as intellectual game. Because somewhere along the way, you stopped taking the world at face value.

You’ve built a career on knowing things. On understanding systems, navigating complexity, making decisions based on information. You’ve learned that expertise matters. That knowledge compounds. That if you pay attention carefully enough, you can understand how things work.

And that’s exactly where this question originates.

Because now you’re asking: What am I understanding? What am I actually paying attention to?

The Map Is Not the Territory

There’s a useful distinction, one you may have encountered before, between a map and the territory it represents.

A map of New York City is not New York City. It’s a representation. A useful one—you can navigate by it, plan by it, understand the city’s structure through it. But no matter how detailed the map, it is fundamentally different from the actual experience of walking through Times Square at rush hour, feeling the humidity, hearing the cacophony, sensing the human density.

The map is information. The territory is reality.

Here’s where this becomes interesting for you, right now, in this moment of your life:

Almost everything you know about the world comes through maps. Not literal maps, but representations. Language. Concepts. Categories. Stories. The neural patterns your brain has learned to recognize and label as “real.”

When you see a friend’s face, you’re not seeing their face directly. You’re seeing light reflected from their face, processed through your eyes, interpreted by your visual cortex, recognized against patterns stored in your memory. What you experience as “seeing your friend” is actually an extraordinarily complex act of construction. Your brain is building a map of what’s there.

This isn’t a flaw. This is how perception works. It has to work this way. Your brain couldn’t process the raw, unfiltered totality of reality. It would be overwhelming, unusable. So instead, your nervous system filters, simplifies, categorizes. It creates maps.

But here’s the question that won’t leave you alone: How much of what you call “reality” is actually the territory, and how much is the map?

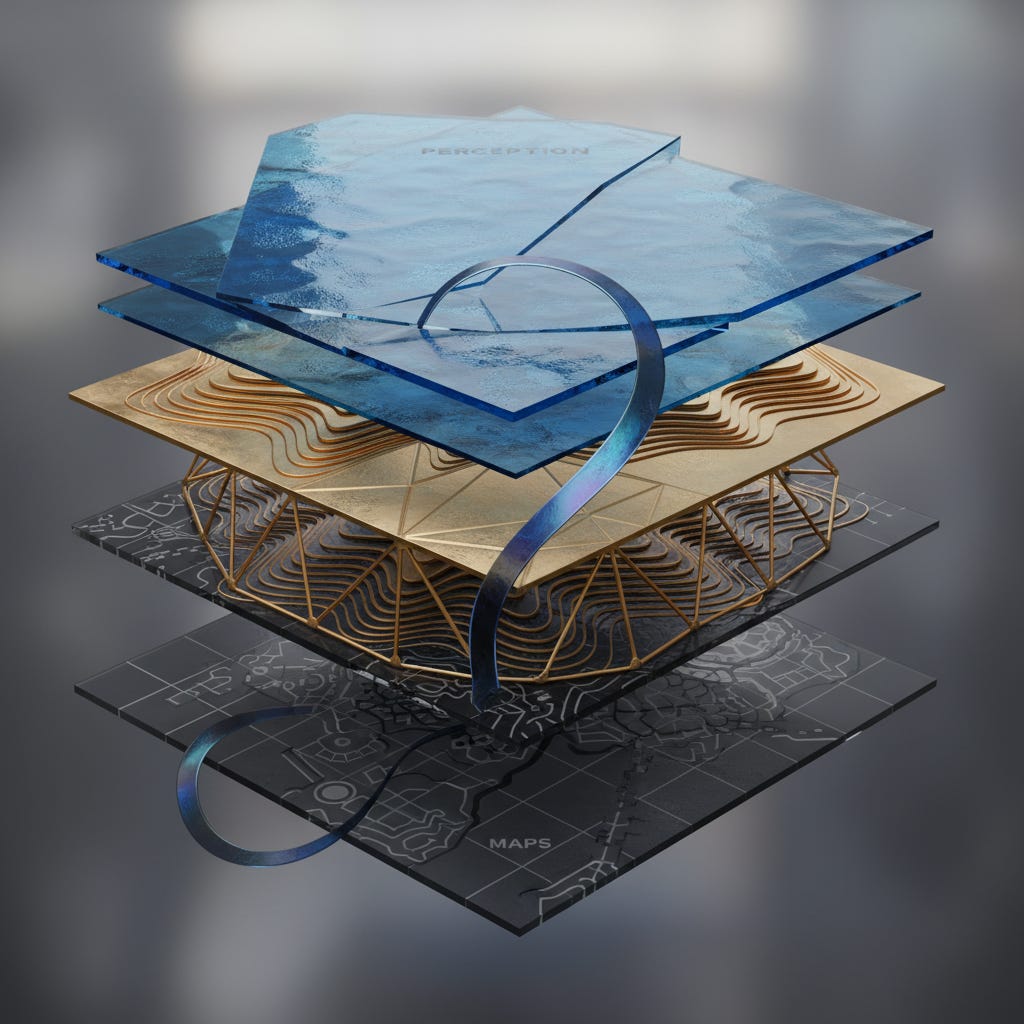

Three Layers of Reality

Let’s think about this carefully, because it matters.

Layer One: Physical Reality

There is something here. A universe. Matter and energy arranged in patterns. Physics describes these patterns with increasing precision. Quantum mechanics reveals weirdness at the smallest scales. General relativity describes the structure of space and time at the largest. There are laws, or at least patterns, that hold consistently whether anyone is observing them or not.

When you weren’t born yet, the Earth was still here. The laws of thermodynamics were still operating. Gravity was still pulling things together. This suggests something independent, something real apart from your perception of it.

This is the territory. The actual, objective physical structure of reality.

But—and this is important—you never access this layer directly. You access it through measurement, through instruments, through models. A physicist doesn’t directly “see” an electron. They see the trails it leaves in a detector. They build mathematical models that predict behavior. The models work extraordinarily well. But they are still maps. Extraordinarily useful maps, but maps nonetheless.

Layer Two: Experienced Reality

This is the world as it appears to you. Colors, textures, emotions, meaning. The feeling of sunlight on your skin. The way a piece of music can move you to tears. The sense that your life matters, that some things are worth doing and others aren’t.

This layer is real. It’s not an illusion. But it’s constructed. Your brain is actively making it.

When you see the color red, you’re not perceiving red as it “actually is” in the physical world. Red is a wavelength of light. Your brain interprets that wavelength and generates the experience of redness. A person with color blindness experiences the same wavelength differently. Neither of you is accessing “what red really is.” You’re both having your brain’s particular construction of that wavelength.

And yet the experience is real. Your subjective reality—the world as it appears to you—is undeniably real. You live in it. It shapes your choices, your feelings, your sense of meaning.

Layer Three: Conceptual Reality

This is the realm of meaning-making. Language. Stories. Categories. Values. The way you’ve learned to group things and make sense of them.

When you use the word “self,” you’re pointing to something real about your experience. There is a continuity to your experience over time. There is a perspective from which you see the world. And yet the “self” is not a thing you can locate. Neuroscientists can’t find it in your brain. Philosophers can argue endlessly about what constitutes it.

And yet you live as though the self is real. You make decisions “for yourself.” You feel responsibility for your past actions. You have a sense of who you are.

This layer too is real. But it’s constructed. It’s the meaning your mind has woven out of the chaos of experience.

So What Is Actually Real?

This is where honesty becomes important.

The answer is: All three layers are real. But they’re real in different ways.

The physical universe exists independently of your perception. That’s real in a fundamental sense.

Your experience of that universe—the colors, the feelings, the sense of aliveness—is real. It’s what you actually live in, moment to moment.

And the meanings you construct—the categories, the stories, the sense of purpose—are real too. They shape your behavior. They matter.

But they’re also made. You participate in constructing them.

Here’s what this means, practically speaking:

You cannot access reality directly. You live in your maps. Your perception of the world is not the world itself—it’s your brain’s construction of the world.

This could be terrifying. It could lead you to radical skepticism: “If I can never access reality directly, how can I know anything?”

But there’s another way to think about it.

Your maps are constrained by the territory. You can’t just believe anything and have it work. The physical world pushes back. If you believe you can fly and jump off a building, gravity doesn’t care about your belief. The territory is real, and it enforces constraints.

This is how you know your maps are tracking something real: they work. They allow you to predict. They allow you to act effectively. They allow you to build bridges that don’t collapse and medicines that actually heal.

The scientist’s map of the atom isn’t “the truth” in some absolute sense. It’s a model. But it’s a model that works. It makes accurate predictions. It reveals patterns that hold true across countless experiments. The map is tracking something real about the territory.

And your lived experience—the world as it appears to you—works too. It guides you. It tells you things that matter. When you feel love, that feeling is real, even though it’s constructed from neural patterns and memories and hormones. The map is tracking something real about your inner territory.

What Changes When You Really Ask This Question

You’re asking this question now, in the second half of your life, because something has shifted in you.

You’ve built a career on expertise. On having answers. On knowing things. And you’ve done well at it. But somewhere along the way, you’ve begun to sense the gap between the maps and the territory. You’ve noticed moments when the map breaks down. When your carefully constructed understanding doesn’t quite capture the full reality of what’s happening.

When you’re with someone you love, no amount of psychology or neuroscience fully explains the experience of love.

When you face your own mortality, no amount of rational planning fully contains what that means.

When you encounter genuine beauty, no explanation fully captures why it moves you.

These gaps are real. They’re not failures of explanation. They’re invitations.

The invitation is to stop insisting that the map is the territory. To develop humility about what you can know and what you can’t. To distinguish between:

What you can measure and quantify

What you can experience directly

What you can only understand conceptually

What remains fundamentally mysterious

And to hold all four of these as valid forms of reality.

Beginning the Journey

You’ve spent decades building expertise. Narrowing your focus. Getting very, very good at specific things.

This year, we’re going to reverse that for a while. We’re going to broaden the inquiry. We’re going to ask the biggest questions, the ones you deferred while you were busy building.

And the first question—the one that everything else depends on—is: What is actually real?

Not as abstract philosophy. As practical inquiry. Because how you answer this question shapes everything. It shapes what you pay attention to. What you consider important. What kind of life seems worth living.

You can’t access reality directly. But you can get very, very good at noticing the gap between your map and the territory. You can develop sensitivity to moments when the map breaks down. You can learn to hold multiple maps at once—the scientific, the experiential, the conceptual—without demanding that they all be the same thing.

And in that gap, in that humility, something opens up.

Not certainty. Not final answers. But something more valuable: genuine inquiry. The capacity to keep asking, to keep noticing, to keep refining your understanding of what’s real.

That’s what we’re beginning, right now.

What is reality?

Keep that question close. Not to solve it. But to let it reshape how you see everything.

For the Next Essay

We’ll go deeper. We’ll ask: Why is there something rather than nothing? What does that question actually mean? And what does the answer—or the impossibility of answering—tell us about the nature of existence itself?

For now: Notice the gap between your map and the territory. Notice moments when your understanding doesn’t quite capture the full reality of what you’re experiencing. Those moments are real. They’re invitations.

Pay attention to them.